Clive D. A. Smith, eternal Chancres vocalist, also known as The Myth under band member naming conventions, submits this reminiscence. His by-line is “Clive Thmith talk like thith” in the Name Song.

The creative contributions of CDAS included inspiring guitarist Greg to write The Road to Hell (see Lyrics 22). Clive had laboured hard in the hot sun for hours laying paving stones at their verdant Yarralumla residence close to the official namesake residence of the Governor-General, telling Smith patriarch Rodney he would mow the lawn later. Rodney somewhat critically thundered “The road to hell is paved with good intentions!”

Clive also wrote lyrics for the classic semi-funk experimental “not punk” ballad San Francisco, the tale of Jimmy, leaving the Village on a Greyhound bus, with Persian socks (see Lyrics 16, they were only living), and ad libbed effectively, including with classic Airbus (Lyrics 18).

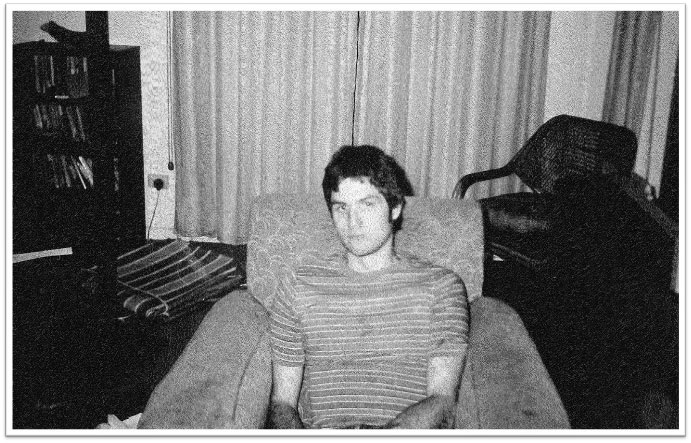

A dent in my face

Gaining secure employment in 1980 Canberra was very hit and miss. I did secure employment, but the job required sitting or standing for hours with almost nothing to do. I was an attendant opening the doors leading from Kings Hall into the Senate in Old Parliament House as well as running office errands. The attendants had recently been told they weren’t allowed to spend their afternoons drinking in the non-members bar. To some of them this seemed to be very unfair because that’s what they’d been doing for decades. I understand they may have even approached the union.

One Friday in late 1980 there was a Happy Hour at the old Hotel Canberra, now the 5 Star Hyatt Canberra. Parts of the building were used for office space, but it was mostly empty and slightly dilapidated, with plenty of room to set up tables and beer kegs. The Chancres were playing at the Wesley Centre on National Circuit that night so I couldn’t stay long but nonetheless I’d drunk enough in the time I was there so that on the way home I rode my pushbike at usual breakneck Tour de France speed into the rear of a stationary car parked on Captain Cook Crescent, Griffith, near the rented 1950s puce brick band house. It was a Celica, perhaps Sillycar, I think, and the impact left a small dent in the bumper bar and a big dent in my face, with grazing and general lacerations. The bicycle was bent too, and I had to sling it over my shoulder as I staggered the remaining distance to seek succour for my wounds.

Chief Chancrette Jane took me to Woden Valley hospital, but they didn’t stitch one of the cuts or clean it out, leaving me with a lifelong blueish tear drop shaped scar next to my right eye, embedded bluestone road gravel. People have asked me if this distinctive scar is from prison time. Ask me no questions I will tell you no lies. I don’t remember much about that gig or the night but having fresh and real facial injuries did help add to the punk atmosphere, and from all reports the crowd went off like a firecracker. Performing in a bloodstained Senate attendant uniform shirt also established street cred with the local punters, symbolic of the backstabbing continuing to this day in the parliamentary chamber of unrepresentative swill.

Musical Achievements and Evolution toward The Chancres

Winning second place in the 1971 Canberra Eisteddfod at the Griffin Centre in Civic (under 11 boys singing) and a widely applauded performance at the end of year school concert at the Canberra Theatre in 1972 could have been the end of a promising singing career, had I not by pure happenstance been in the same Stirling College economics class as Mark Jarratt and Greg Powell in 1978.

Both had a distinct fashion style, Greg wearing Hard Yakka shirts and shorts channelling perhaps a golf course groundsman or nurseryman while Mark’s attire had more militaristic themes, with crewcut, highly polished boots and army surplus courtesy of his dad. This stood out in the sea of blow-dried long hair, windcheaters, grey Levis “Californians” jeans and running shoes worn by most at Stirling College including yours truly (except for our ginger nut mate and bassist Christopher Paxman; his preferred clobber was sort of Kalgoorlie Rajneeshi orange person). They were also writing original music, a distinct style, forged in Weston on the slopes of Oakey Hill. If the words to the first Chancres songs were not written by Mark and Greg they were written by Shakespeare, Thomas Hardy or Kenneth Slessor or in one case Sham 69 (but then only some of them), subject to poetic licence for musical coherence.

Gradually, although with the effluxion of decades I can’t recall all the details, Guy Morrison and later Chris Paxman found themselves playing bass to the unique Chancres economic punk music while I found myself shanghaied into singing behind a microphone. I think I would describe my delivery less as singing and more declamatory poetry slam. Listen to our live recordings and pass your own judgment.